|

|

A screwpile lighthouse stands on pilings that are screwed into a sandy or mud bottom, typical of the ones in the sounds of North Carolina. Up until the late 1800s there was enormous commercial traffic on the sounds, which only gradually gave way to railroads and then highways. Before the Civil War, lightships marked the shoals and junction points of North Carolina's coastal rivers and sounds, but after the war the United States Lighthouse Board made a concerted effort to replace them with screwpile lighthouses. Many were installed in the years immediately after the war, and others added all the way into the early 1900s. All were decommissioned and removed by the 1950s, to be replaced with lighted markers, sometimes on the same foundations.

The earliest screwpile lighthouses were hexagonal, but most of the North Carolina structures were square. The first floor was broken up into small rooms for cooking, storage and office space, while the second floor (essentially an attic, under the roof pitch) provided sleeping space for the keeper and his family, and above was a small room with windows on three sides for observation. On the fourth side was a passageway that led out to the bell platform. Above all was a cupola housing the light. A central spiral staircase allowed access to the various levels. The house was surrounded by a porch, on one side of which was an outhouse and on the other, a storage shed. Below the house was a platform open to the elements for storage and for livestock - generally, chickens and goats. Boats hung in davits and there were ladders to the water. Reportedly the houses were prefabricated at a location in the north and assembled on site. One source suggested that the prefabrication was done at a leper colony in New England, but I have not been able to find documentation.

The Lighthouse Board, part of the Department of Treasury, was in operation from 1852 to 1910, and was responsible for all aids to navigation, including buoys, day markers. The Lighthouse Board replaced an earlier Treasury arm known as the Lighthouse Establishment. Stephen Pleasonton ran the Lighthouse Establishment for 30 years. He was known for thrift, and during his tenure very little progress was made in the development of aids to navigation. Most notoriously, he refused to consider the use of Fresnel lenses in place of the far inferior Lewis lenses then in use. By the 1840s, shipping interests were close to active revolt over the condition of our nation's aids to navigation, and Congress finally acted. Pleasonton was well enough entrenched that it took four years for Congress to enact the new law establishing the Lighthouse Board.

As an aside, Pleasonton's thrift had beneficial as well as deleterious effects. As the British approached Washington D.C. in 1814, he removed the original Declaration of Independence and Constitution, as well as the records of State Department, to a safe place in Virginia, preserving them from almost certain destruction when the city was burned.

Despite its position in Treasury, the Lighthouse Board was a quasi-military operation, with representatives of the Navy, Coast Survey and Topographical Engineers, plus noted scientist and surveyor Alexander Dallas Bache on the original board. At the time, the military was at the forefront of technology and engineering, and the Lighthouse Board did yeoman work over the years. It was finally dissolved in 1910 and reconstituted as the civilian Lighthouse Service under the Department of Commerce, which itself was merged into the Coast Guard in 1939.

In the early years of the 19th century Ocracoke Inlet was a major point of entry for overseas trade. Ships would put in to Portsmouth where their cargoes would be transloaded onto shallow-draft vessels capable of navigating the sounds and rivers of eastern North Carolina. These vessels would then return to Portsmouth with the agricultural product of the hinterlands for export. There were three major routes out of Portsmouth - one south to the Core Sound, one west to the Neuse and Pamlico Rivers, and one north to the Albermarle. North Carolina commercial interests begged and pleaded with the state government to provide aids to navigation, to no avail, and eventually the federal government stepped in. Between 1825 and 1836 the Lighthouse Establishment put in service nine lightships and two lighthouses to mark the major channels and shoals of the North Carolina sounds. Just before the Civil War, the newly enacted Lighthouse Board built the first four screwpile lighthouses in North Carolina, including one at Northwest Point Royal Shoals to replace a lightship.

During the Civil War, the Pamlico Sound lightships were all sunk or removed by the confederates, as they were of more use to the federals, but it must have been a hard thing to do. Now the states in revolt were destroying the very things they had begged for. It says much for the forbearance of the federal government that it promptly replaced the needed aids to navigation once the war was over.

|

A Lighthouse Board report from 1871 lists five screwpiles on Pamlico Sound - Brant Island Shoal Lighthouse, Northwest Point Royal Shoal Lighthouse, Neuse River Lighthouse, Long Shoal Lighthouse and Harbor Island Lighthouse.

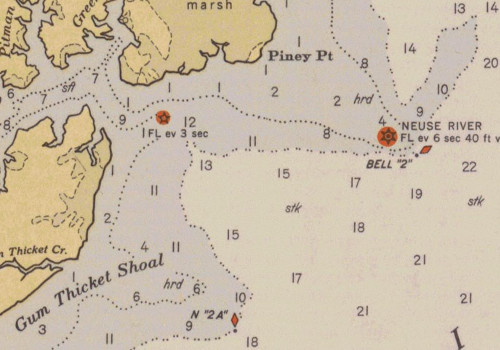

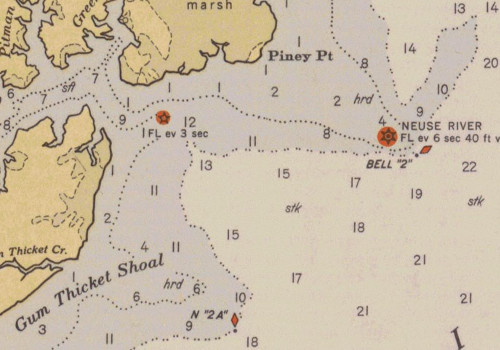

The modern-day marker "NR" is off Point of Marsh but the Neuse River Lighthouse was across the river off Piney Point at the mouth of Lower Broad Creek, near current Marker 4. The structure still existing there that is commonly described as an abandoned range marker is actually the remnants of the old lighthouse. The structure showed a fixed white light 52 feet above water visible for 12 miles in good conditions, and there was a bell for fog that could be heard five miles away. The bell rang on a clockwork mechanism four times a minute. Winding the clock with a giant crank took ten minutes, and the bell would ring two and a half hours on a winding. The clock mechanism had 15 hundred-pound weights in it. At least once during a long spell of bad weather the bell was rung 60 hours straight. Locals called the Neuse River Lighthouse "the grasshopper" for its spindly appearance. While some sources state this lighthouse was constructed in 1862 or 1867, a more likely date is 1869. There is good documentation that it replaced the lightship off Point of Marsh which had marked the entrance to the Neuse River since 1828. The Lighthouse Board report of 1871 lists a "Buoy on Point Marsh (Light Vessel Station)". I have no information that there was ever a screwpile lighthouse at this location, even though most of the lightship locations eventually got a screwpile replacement. Almost certainly the Neuse River Light off Piney Point superseded the lightship. Neuse River Lighthouse was dismantled in 1931, and perhaps at that time the "NR" designation reverted to the Point of Marsh location. There is an enormous "NR" marker off Point of Marsh now.

The current marker off Pamlico Point, "PP", stands on the foundations of the screwpile Pamlico Point Light, which may have been constructed in 1891. The late construction could be accounted for by the fact that a brick lighthouse dating back to the 1820s already existed on the nearby shore. The Lighthouse Board report of 1871 lists Pamlico Point Lighthouse as a "white tower", probably the whitewashed brick structure.

|

There were two screwpiles on Royal Shoals, Northwest Point and Southwest Point. Northwest Point was a very early one, reportedly built in 1857. The first screwpile lights built were in England in the early 1840s. The first in America was the Brandywine Shoal Light in Delaware Bay, completed in 1850. There is no mention of the Southwest Point Royal Shoals light in the 1871 report, so evidently it was built at a later date. Northwest Point was abandoned in 1903, and there is an extant picture of it in derelict condition in 1922.

Harbor Island Lighthouse marked the entrance to Core Sound from Pamlico. It replaced a lightship on the same location.

The last lighthouse on the 1871 list, Long Shoal, was up the sound near Engelhard, on the way to the channel to the Albermarle, through the "Croatan Marshes". This was a dangerous place for shipping, and the first and largest of the Pamlico Sound lightships served from 1825 until the Civil War.

The 1871 report lists buoys at two locations that later got screwpile lights - Bluff Shoal and Gull Rock Shoal. Bluff Shoal may have been one of the last screwpiles constructed , if the date given of 1904 is correct. Gull Rock Shoal is now simply Gull Shoal, guarding the entrance to Wysocking (formerly Yesoken) Bay.

|

One obscure screwpile light stood on Oliver Reef near Hatteras Inlet. A reference shows that it was built in 1874, and Eldridge's Coast Pilot of 1882 states that the light was intended to guide sailors from the Pamlico Sound into Hatteras Inlet. A dramatic story has come down about this light. In 1917, the sound iced up and Oliver Reef Light was isolated for 30 days. Then, as the ice broke up, floes jammed around the Light and severely damaged it. Joe Burrus of Hatteras was manning the Light, and he was rescued by Captain Charles MacWilliams, who later went on to run the Outer Banks Mail Service. Burrus in later years was the keeper of the Hatteras Light.

Another screwpile, Roanoke Marshes, stood at the junction of Pamlico and Croatan Sound. It was built in 1877 as a replacement for earlier lights that had been destroyed. According to a Raleigh News and Observer article from 1953, Roanoke Marshes was the last manned screwpile in operation. The newspaper article noted that it had a crew of three, two of whom were on duty at all times. According to the article, Wade's Point had been manned until recently, and all others had been "made automatic" at earlier dates. This suggests that at least some of the screwpiles may have been operated as unmanned stations with electric power before being replaced with modern lighted markers. After Roanoke Marshes was decommissioned, it was sold to a private individual who attempted to move it, but it toppled off the barge in rough seas and was abandoned. In 2004, the town of Manteo completed a replica of the Roanoke Marshes Light which can be seen on the town waterfront.

Every screwpile listed still has some kind of marker at the location, evidence of the stability of the natural formations in the sound. Since several screwpiles replaced lightships that were instituted in the 1820s, that means that in some locations there have been aids to navigation in place for 185 years.

|

Albermarle Sound had its share of screwpiles as well, and the last surviving of the original North Carolina screwpile lights is at Edenton. This one is atypical in design, somewhat larger than most of the others and with a light tower rather than the more-common cupola. There is speculation that it was built for the Great Lakes but ended up in North Carolina due to urgent need. Once marking the entrance to the Roanoke River, this light was decommissioned in 1941 and ended up in private hands. The owner moved it to shore and lived in it until his death 50 years later. Eventually his heirs sold it to the Edenton Historical Society, who moved it to Edenton. The town of Plymouth had tried to buy it earlier, but ended up building a replica of a predecessor light. Anyone interested in the screwpile lights could spend a profitable day on the Albermarle visiting these two structures.

There are no more working lighthouses on the inland seas of North Carolina, and even the memory of them is fading. A Neuse River sailor can still imagine, though, what it was like to sail across the Pamlico Sound with nothing more than a distant white light to guide him.

Sources:

List of Beacons, Buoys, Stakes, and Other Day-marks in the 5th Lighthouse District

F. Stanly Commodore U.S. Navy

Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 1871

North Carolina Lighthouses

David Stick

North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources

Division of Archives and History

Raleigh, NC 1980

ISBN 0-86526-138-5

North Carolina Lighthouses and Lifesaving Stations

John Hairr

Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, SC 2004

Raleigh News and Observer

Sunday Morning, May 17th, 1953

Eldridge's Coast Pilot

S.Thaxter And Son

Boston, 1883

Doward Jones, Jr.

Roanoke River Lighthouse and Maritime Museum

Plymouth, NC

Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center

Harkers Island, NC

The History Place

Morehead City, NC

North Carolina Maritime Museum

Beaufort, NC

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Screw-pile_lighthouse

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Lighthouse_Board

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Dallas_Bache

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Pleasonton

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roanoke_River_Light

http://www.lighthousedigest.com/Digest/database/searchdatabase.cfm

http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=359

http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=880

Neuse River Light and Roanoke Marshes photographs courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard - http://www.uscg.mil/history/weblighthouses/. Other photographs by Paul M. Clayton.